In general, I’m a fan of my internal organs remaining, well, internal. Our bodies are so complicated and extraordinary that if something is there it must have a purpose, otherwise it wouldn’t be there. Even if medical science does not yet understand what it is.

I know, I’ve heard the theories about our pinky toes slowly evolving out of the body (women’s shoe designers cannot wait for that moment I’m sure) or the uselessness of, say, the appendix. But then, after years and years of yanking the appendix out of our bodies with nary a second thought, it turns out that it might possibly be an incredibly useful storehouse for “good” bacteria and fires into business right when we need it most: during illness.

So when a man in a white coat with his name embroidered on the left breast with the word “Surgery” underneath tells me that I have an organ with no purpose, I’m going to give him the ole fish eye.

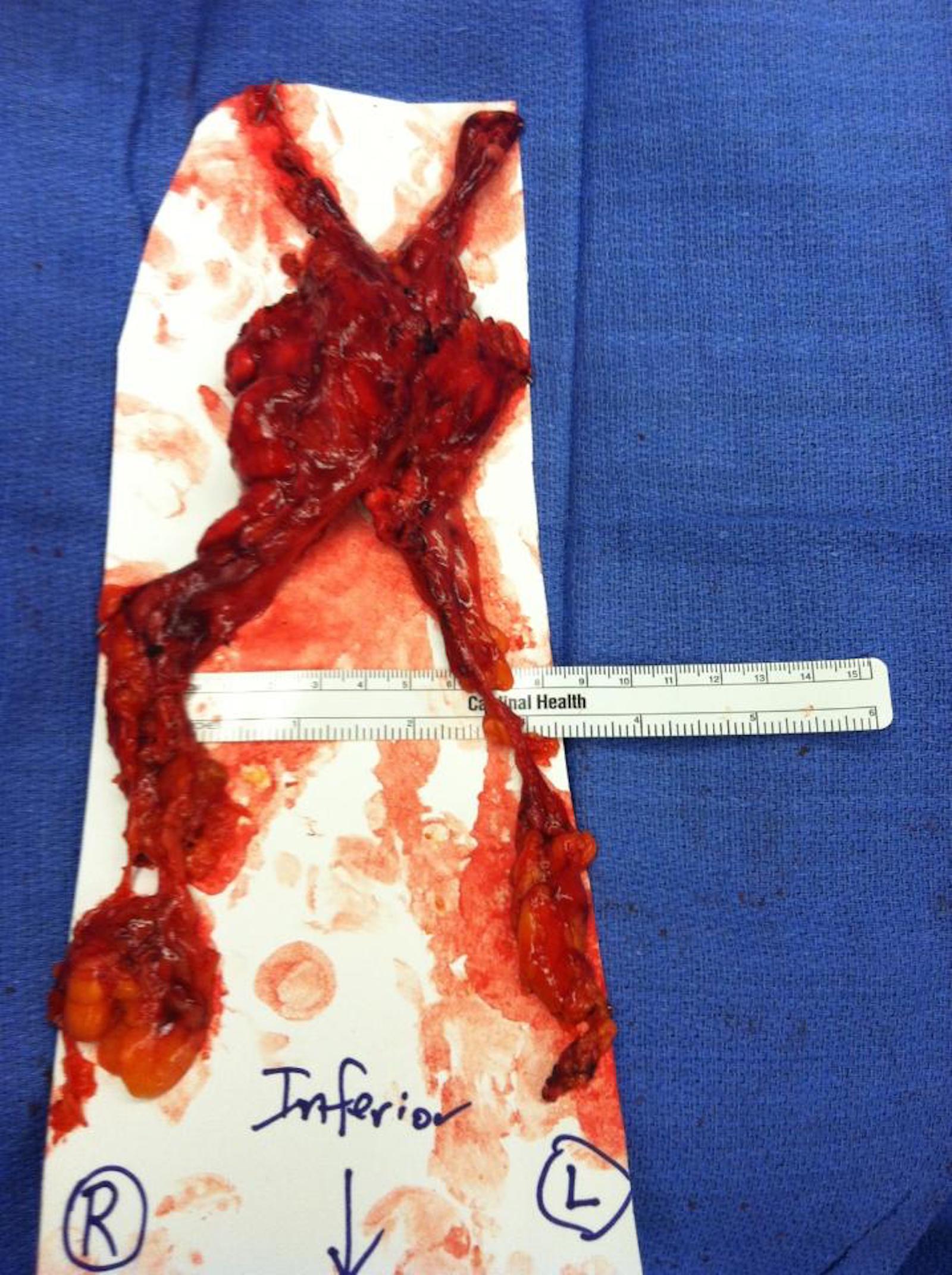

The thymus is an interesting organ for one that I had never heard of before my oncologist wanted to remove it. It is very flat, lying between the heart and the sternum, and has four long arms, two reach up on either side of the neck, and two reach down alongside the lungs. In some pictures, it almost looks like a butterfly. Vitally important when we are young, it produces T-cells, some of our immune system’s fighters. Therefore babies born without the thymus have a terrible time battling illness. Its purpose is gradually replaced (or, perhaps, augmented) by bone marrow as we age, resulting in the thymus shrinking and turning almost entirely into fat by the time we are in our 70s. Therefore, by the time we are in our 70s, the thymus is, in fact, useless. (Unless you believe that it also has a purpose in the endocrine system helping out with hormone regulation. In which case, it remains active until death.)

However, before that fateful day when the thymus self-destructs, it is possible to resuscitate it using herbs and homeopathy, and some studies have shown that adults without a thymus prematurely age. It is not entirely clear how long the thymus remains actively involved in helping the immune system after we reach puberty.

For me, my PET scan possibly showed “thymic rebound,” which means that my thymus was capable of resuscitating itself for at least a few months after having been thoroughly pissed off by chemo. During those few months I’d like to think that it was helping out when my bone marrow was too exhausted to do much. Neupogen, the drug that I was on to help with my immune system during chemo, only stimulates bone marrow, and eventually bone marrow becomes exhausted, and stops responding as quickly, or at all, to the stimulation. My counts rebounded more and more slowly as chemo went on and today are still not up to average.

Now my thymus is gone, lost to medical slides and dyes and preservatives because the PET scan was too sensitive. It might have already been heading out the door, strangled by a tumor that was, at one point, 12x10x9 cm, and residing in a body that was halfway to 70. But I don’t want you to believe that I let it go quietly into that good night. We checked and double checked with doctors and surgeons, and I had multiple conversations with my belly-button and friends and my own angels and demons. Even though my thymus was quiet, I raged, raged against the dying of the light for it.

And then had surgery.

And now write this memorial.

That is one sexaaay thymus, my dear. Much like the rest of your organs, I’m sure.

HA! Without a doubt. 🙂

A beautiful eulogy dear heart, and I’m proud of your ‘fish eye’ re useless organs.

MOM